The Trump Assassination Attempts and the Duels of Andrew Jackson

How Southern Honor Culture Creates a Politics of Violence

Political violence has a long history in the United States, characterized by personal vendettas and battles over ideology alike. From duels fought by the seventh U.S. president, Andrew Jackson, to the recent assassination attempts against Donald Trump, our country has seen how its political figures and their rhetoric can incite, promote, and subsequently become victims of violence themselves.

By comparing the experiences of Jackson and Trump, several important parallels emerge, revealing the deep-seated nature of political violence that has been a fixture of America’s identity since its founding.

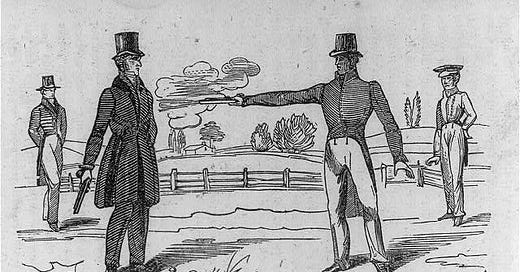

Andrew Jackson served two terms as president from 1829 - 1837 and is often remembered for his short temper and willingness to use violence to settle disputes. Jackson participated in numerous duels, most famously killing Charles Dickinson in an 1806 encounter. These duels, widely publicized at the time, were representative of a political culture where personal honor was tied closely to violence. Jackson’s readiness to fight anyone who challenged him made him a hero to many Southerners, especially after the Civil War when Redeemers celebrated him as the ideal Southern president.

Southern honor culture, which emphasized personal reputation, masculinity, and the defense of one’s honor—often through violent means—remained a powerful force in the post-Civil War South. Jackson’s history of duels, unapologetic approach to violence, and reputation as a tough and uncompromising leader, made him a model of Southern masculinity well after his death in 1845.

This emphasis on personal strength and violence was appealing to the Redeemers, who yearned to reclaim Southern manhood in the aftermath of defeat in the Civil War. During and after Reconstruction, the Redeemers consisted of former Confederates and others who opposed the Union and the Republican Party of Abraham Lincoln and Ulysses S. Grant. To them, Jackson served as a symbol of resistance and resilience, qualities that Redeemers wished to emulate in their efforts to “redeem” the South from Northern domination and return to a pre-Civil War, antebellum status quo.

A strongly held belief in states’ rights was central to Jackson’s political ideology and resonated deeply with Redeemers. His overall commitment to empowering local government made him a champion for those who sought to minimize federal intervention in the South during Reconstruction. His fight against what he saw as federal overreach, especially in economic policy, made him a champion for Redeemers who opposed Reconstruction policies imposed by the North, such as civil protections for the formerly enslaved and a federal military presence in the South.

For Redeemers, Jackson’s defense of states’ rights aligned with their efforts to contain the federal government’s influence, particularly when it came to civil rights and freedoms for Black Americans. They saw in Jackson an early defender of Southern sovereignty, a man who could stand up against the kind of federal authority that Reconstruction had represented.

The image of Jackson as a populist leader who stood up for the “common man” also inspired Redeemers. While Jackson portrayed himself as a protector of the average white settler and farmer, he did so within the racial and class structures of the time, excluding Black people and other non-White groups from his populist vision. As Redeemers attempted to dismantle Reconstruction-era civil rights advancements and return the South to its pre-war status, they embraced this narrative. They praised Jackson as a figure who could symbolize their vision of a racial hierarchy through policies like the Indian Removal Act, which exemplified the exact kind of racial exclusion and white expansion that the Redeemers sought to restore.

In the same way that Jackson embodied the violent ethos of his time, Donald Trump has become a symbol of modern political aggression today. Throughout his political career, Trump’s rhetoric has repeatedly incited violence, whether at campaign rallies where he encourages supporters to “beat up” hecklers or on January 6 when he told protestors, “If you don't fight like hell you're not going to have a country anymore.” Trump’s casual endorsements of violent acts—against immigrants, protestors, and political opponents—have intensified the division in an already polarized political environment.

Not unlike Jackson’s era, where confrontations often resulted in death or injury, Trump’s rise to power has coincided with a national culture where violence is not only tolerated but normalized, and political leaders might have to engage in duels, or a life-threatening confrontation.

After Reconstruction, Redeemers worked to memorialize Jackson as a symbol of white Southern defiance across the nation. Throughout the South, they still celebrated Confederate leaders and soldiers, but these Southern icons could not have national appeal. Jackson died two decades before the Civil War ended, therefore he could be a Southern icon but not a Confederate. In 1928, Jackson’s national memorialization was secured when he became the face of the $20 bill.

Trump, in many ways, adopted Jackson’s image, even placing a portrait of Jackson in the Oval Office during his presidency. Trump also opposed the removal of Jackson from the $20 bill and replacing him with Harriet Tubman. Trump and Jackson have both claimed that they have been cheated out of the presidency: Trump in 2020 and Jackson in 1824. Both men have inspired fierce loyalty and violent opposition, representing a unique kind of American populism that equates strength with aggression. If Trump wins the presidency again do not be surprised when his supporters proclaim that his face should also adorn our currency.

For Jackson, violence was personal—his duels were often fought over personal slights or challenges to his honor. For Trump, violence is both personal and ideological and rooted in the divisive words he uses to rally his base. Trump often describes his legal troubles as personal attacks and has stated that he will seek revenge against his political enemies.

Jackson’s duels were a form of political theater, just as Trump’s violent rhetoric serves as a spectacle for his supporters. Both Jackson and Trump used violence, whether physical or verbal, to assert power and control, and in doing so, created environments where their opponents—and sometimes even their supporters—resorted to violence as well.

Recently, however, the political violence surrounding Trump has taken a new turn. In the past three months, there have been two assassination attempts against him, prompting questions about the broader implications of violence in today’s political landscape.

Unlike the duels of Jackson’s time, the violence directed towards Trump is more widespread, fueled by a culture of anger and division. An increase in the activity of extremist groups like the Proud Boys and other KKK-affiliated organizations, alongside bomb threats and acts of political violence across the country, can all be traced back to the strong feelings of anger that Trump evokes among his supporters and opponents alike.

Neither of Trump’s attackers has espoused clear political views that could align them to either major political party. Instead, Trump’s two attackers–Ryan Wesley Routh and Thomas Matthew Crooks–fit the profile of angry white men who wanted to engage in a duel with Trump to preserve either their own or the United States’ honor.

Trump’s political rise has turned politics into an existential battle, where opponents are viewed as not just wrong—but as dangerous enemies who must be defeated. This kind of thinking, amplified by the availability of guns, creates a volatile environment where political violence is not only possible but expected: where political leaders are expected to incite, engage in, and prevail against duels to the death.

The parallels between Jackson and Trump reveal a troubling continuity in American political violence.

In their own ways, both figures have used violence to assert their political dominance with significant consequences. Just as Jackson faced numerous threats on his life, Trump now finds himself the target of assassination attempts. The normalization of violence, both in the past and present, is evidence that political violence is not a new part of American history—it is an enduring aspect of our political culture.

As long as leaders continue to promote, tolerate, or engage in violence, the cycle will only continue.