Much of The Reconstructionist focuses on Barrett Holmes Pitner’s theory of the American Cycle, which helps explain how and why America’s current political crisis mirrors the aftermath of the collapse of Reconstruction in 1877.

As President Donald Trump aggressively implements his regressive agenda, the parallels between the past and the present have become abundant and unmistakable. To highlight these parallels, we will publish The Reconstructionist Weekly each Monday, summarizing the regressive policies that undermine our democracy and how they mirror the past.

Also, next Wednesday, April 16, at 1 pm, the Reconstructionism Project of the American Bar Association will host a free webinar titled By Understanding Reconstruction, You Understand the United States: A Discussion with Daryl Atkinson and Barrett Holmes Pitner. This event will be a great opportunity for learning more about the parallels between the past and the present, and how we can make a more equitable, just, and free America. You can register for the free event here. You can also watch all of the previous events in this series here.

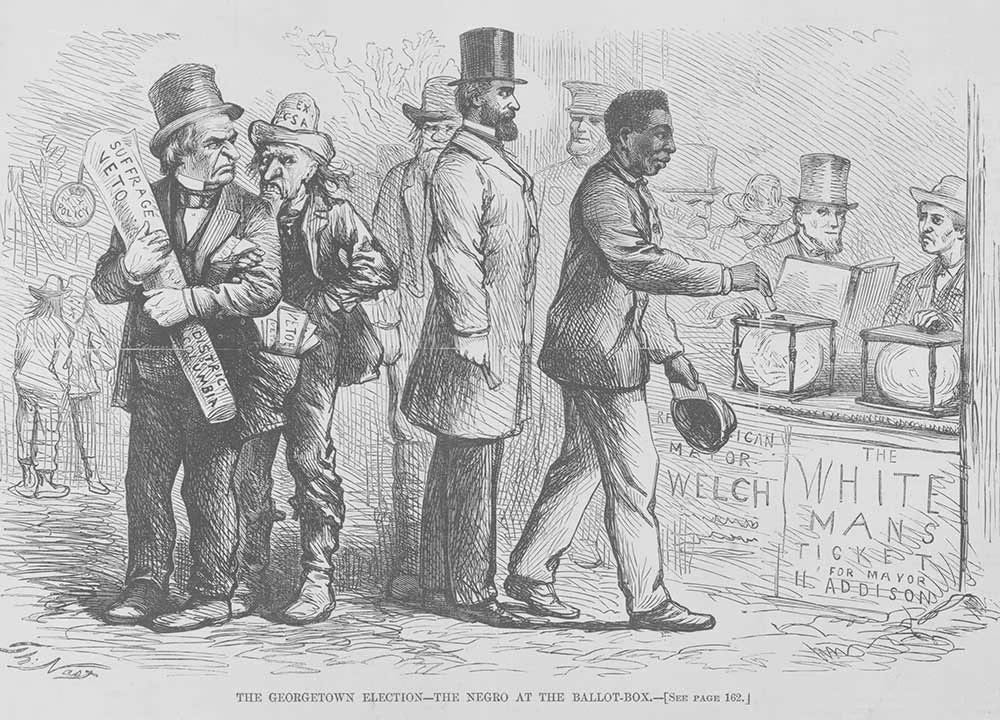

Then → After Reconstruction, white supremacists in the South methodically worked to dismantle Black voting rights through a sophisticated system of voter suppression. Despite the 15th Amendment’s guarantee that voting rights, “shall not be denied or abridged…on account of race, color, or previous servitude,” Southern states exploited their new authority to determine voter qualifications. This resulted in the disenfranchisement of many Black voters across the region.In Mississippi, where nearly 70% of Black male voters had registered to vote in 1867, but after the collapse of Reconstruction in 1877 and the creation of new voter suppression policies only 9,000 of the 1470,000 voting-age Black Americans qualified to vote in 1890. Louisiana’s disenfranchisement was even more extreme. By 1920, Black voter registration in the state plummeted from 130,000 in 1898 to just 1,342—making up only 1% of eligible Black voters.

Methods of disenfranchisement varied by state, but they all shared a common purpose. Poll taxes placed an economic barrier to voting that disproportionately affected formerly enslaved people. Literacy tests and “understanding clauses” required potential voters to read and interpret complex legal passages or state constitutions. These tests were administered subjectively, and Black voters routinely failed them regardless of their actual literacy. The all-white Democratic primary, which prevented Black Americans from voting in primary elections, was another method of voter suppression that barred Black participation in the only meaningful elections in the one-party South.

Despite all of the civil rights gains achieved by Reconstruction, these tactics, alongside ballot box stuffing and violent intimidation by groups like the Klu Klux Klan, led to the widespread disenfranchisement of Black Americans in the South. These discriminatory practices were deliberately written to appear race-neutral on paper, while in practice, they targeted any non-white voter.

The 15th Amendment gave specific reasons why a person’s right to vote could not be taken away, and in response, racist Americans merely invented new methods for depriving Black people of their right to vote. As a result, the United States has normalized voter suppression tactics that can appear to be race-neutral but create racially divisive outcomes.

Now → The Trump Administration’s SAVE (Safeguard American Voter Eligibility) Act represents a modern version of the voter suppression tactics used by Redeemers in the post-Reconstruction South. Recently introduced in the House, the legislation requires proof of U.S. citizenship for all voter registrations and mandates that states verify citizenship status before allowing individuals to vote in federal elections.

Like its historical predecessors, the SAVE Act employs a seemingly race-neutral approach—preventing non-citizen voting—while implementing requirements that disproportionately impact communities of color, low-income voters, and naturalized citizens. The law requires documentary proof of citizenship beyond what was previously required under the National Voter Registration Act, creating new barriers to registration that echo the ones implemented post-Reconstruction.

Just as poll taxes and literacy tests were supposedly designed to ensure “qualified” voters participated in our elections while targeting Black Americans and suppressing their voter turnout, the SAVE Act similarly addresses the virtually non-existent problem of non-citizen voting while creating substantial obstacles for eligible voters. According to a Brennan Center for Justice survey, documented cases of non-citizen voting are exceedingly rare—fewer than 0.0001% of votes cast in recent elections. This mirrors how post-Reconstruction voting restrictions were justified by unfounded claims of Black voter fraud and incompetence.

The requirement to provide passport numbers, naturalization certificate numbers, or birth certificates places a disproportionate burden on naturalized citizens, who are predominantly people of color. Those without ready access to these documents—often those with lower incomes, the elderly, and individuals who have experienced housing instability—face de facto disenfranchisement. Similarly, these requirements could have a significant impact on citizens who have changed their name, such as married women. A woman whose name on their driver’s license does not match their birth certificate could also become de facto barred from voting due to these new voting impediments.

The SAVE Act further echoes the post-Reconstruction era by empowering states to purge voter rolls of anyone they deem unable to sufficiently prove citizenship, reminiscent of how Southern registrars were given broad discretion to determine who passed literacy and understanding tests. If passed, it is more than likely that states implementing the SAVE Act will see significant drops in voter registration rates, particularly in communities with large immigrant populations, echoing the dramatic decline in Black voter registration in the post-Reconstruction South.

Like the architects of post-Reconstruction disenfranchisement, proponents of the SAVE Act frame it as a measure to protect electoral integrity. However, just as the Regression-era policies were designed to maintain white political dominance, today's restrictions are aimed at suppressing votes from demographic groups that tend to vote Democratic and in favor of a multiracial, multicultural democracy.

In both eras, the assault on voting rights represents a broader effort to reverse progress toward a multiracial democracy. The American Cycle is clearly continuing, as post-Reconstruction disenfranchisement was essential to establishing Jim Crow, and today's voting restrictions support the dismantling of the achievements of the Second Reconstruction.

Reconstructing the Conversation → In addition to stopping the SAVE Act, we should also be thinking about how we can reconstruct our society in a way that cements voting rights protections into law. As modern-day Redeemers continue to attack voting rights, one way we can do this is through a constitutional amendment that proactively protects this essential aspect of our democracy.

Vermont’s state constitution is a great example of a progressive model for voting rights protection. Vermont’s 1793 state constitution ensured that all Vermonters, including the incarcerated, kept their voting rights, and this has been the state’s norm ever since. As a result, it becomes much harder to justify the creation of new voting impediments for non-incarcerated Vermonters.

Vermont's approach stands in stark contrast to most other states, which either temporarily or permanently disenfranchise people with felony convictions. The Vermont model demonstrates how state constitutions or even amendments to the U.S. Constitution can be used to expand and protect voting rights. This will create a foundation for a democracy that recognizes voting as a fundamental right rather than a privilege that can be revoked. Through protecting voting rights and ensuring equal access to the vote, we will continue the legacy of Reconstruction.