The Life of James Rapier: A Forgotten Hero of Reconstruction

Rapier was a champion of civil rights and one of Alabama's first Black congressmen

Following the collapse of Reconstruction in 1877, many of its heroes were disparaged and partially erased from history.

The Reconstructionist works to correct the historical record.

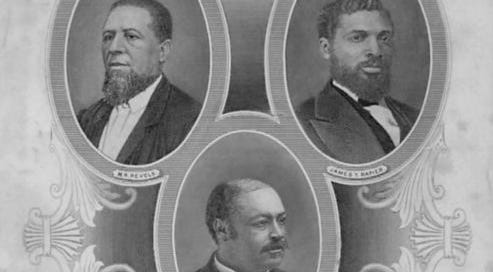

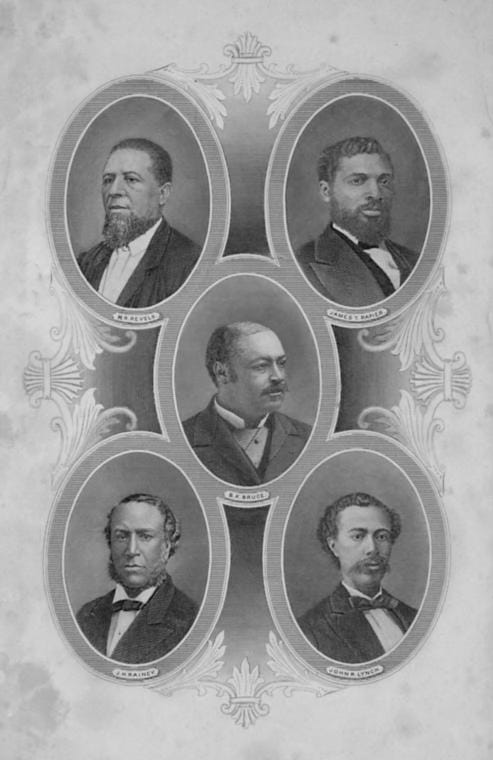

James Thomas Rapier was one of Alabama’s three Black congressmen during Reconstruction. Rapier represented Alabama’s 2nd district from 1873 to 1875.

A successful farmer and politician, Rapier fought tirelessly for the rights of Black Americans, advocating for civil rights legislation and biracial political cooperation. His life and career exemplify both the promises and limitations of Reconstruction, offering a reminder of its continued significance today.

Born in Florence, Alabama, in 1837 to a free Black family, Rapier had access to education that many Black Americans were denied. His father was emancipated in 1829 and had worked as a successful barber for 40 years. Much of his childhood was spent in Nashville, Tennessee where he lived with his grandmother and attended a school for Black children.

To further his education, Rapier moved to Canada and then Scotland, but he eventually returned to Nashville after reading about the events of the Civil War. Determined to use his knowledge and resources for empowerment, he worked briefly for a northern newspaper. Soon after, he purchased 200 acres of land with the help of his father and became a successful cotton planter and businessman. However, his passion for justice eventually led him to pursue a career in politics.

Rapier, During Reconstruction

Rapier became deeply involved in the Republican Party after he attended Alabama’s constitutional convention in 1867. Following the North’s victory in the Civil War, Southern states needed to create new state constitutions since their pre-Civil War constitutions permitted slavery, and for obvious reasons, their Confederate constitutions were no longer legitimate. Rapier was the only Black delegate from his district to attend the convention.

There, he helped shape the new state government, ensuring that the rights of newly freed Black Americans were protected by law. In 1871, he was chosen to be the vice president of the National Negro Labor Union (NNLU) and opened an Alabama branch to advocate for the rights of Black workers.

Understanding the power of the press, Rapier expanded his focus to the media and founded the Montgomery Republican Sentinel in 1872, Alabama’s first Black-owned and operated newspaper. Articles in the Sentinel championed Republican policies, criticized racist Democrats, and endorsed the reelection of President Ulysses S. Grant. When he ran for Congress, Rapier distributed 1,000 free copies of the newspaper a week to spread his message.

Rapier also ran for Alabama Secretary of State in 1870, becoming the first Black candidate to run for statewide office. He ultimately lost the election, but before Election Day, he was approached by a group of white Republicans who offered him $10,000—over $240,000 today—to drop out of the race.

In 1872, Rapier decided to run again, and he was elected to the House of Representatives to represent Alabama’s 2nd district, which had a Black population of less than 50 percent in 1872. According to the 1870 census, 47 percent of Alabama’s population was Black. Once in office, he worked to create a strong, biracial Republican Party in Alabama that would counteract Democratic efforts to disenfranchise Black voters. He was an outspoken advocate for Black civil rights and was one of the seven Black Representatives in Congress who fought for the passage of the 1875 Civil Rights Act.

In a powerful speech on the House floor, in defense of the 1875 Civil Rights Act, Rapier demanded that the United States respect and protect the humanity of Black Americans. “Either I am a man or I am not a man. If one, I am entitled to all the rights, privileges, and immunities common to any other class in this country; if not a man, I have no right to vote, no right to a seat here.”

Rapier’s words were the precursor to the civil rights protests of the 1960s. In 1968, Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. famously marched alongside striking sanitation workers in Memphis, Tennessee, holding signs that proclaimed “I Am, A Man.”

Long before human rights or dignity rights had become concepts in the Western world, Rapier knew that civil rights for Black Americans was more than merely a matter of policy. “Policy is out of the question; it has nothing to do with it. There must be one law for all; that in this case, justice is the only standard to be used, and you can no more divide justice than you can divide Deity.”

Rapier’s advocacy extended beyond just voting rights. Throughout his time in Congress, he advocated for equal access to public accommodations, schools, and even cemeteries, arguing that discrimination in any form degraded the oppressed and the nation itself. He hosted strategy meetings at his Washington home and worked relentlessly to push the Civil Rights Act through Congress.

Despite his efforts, the political tides soon began to turn against Reconstruction. White supremacist violence, carried out by groups like the Klu Klux Klan, escalated dramatically. Rapier himself faced constant threats, and in his 1874 re-election campaign, violent intimidation of Black voters led to his defeat. Democrats used both physical and economic coercion to suppress the Black vote, and plantation owners refused to hire Black workers who supported Republicans. More than 100 people were killed in election-related violence, and Rapier lost his seat by just over 1,000 votes. With Democrats regaining control of Alabama and the federal government scaling back its commitment to Reconstruction, Rapier became increasingly disillusioned about the future of Black Americans in the South.

Rapier, Post-Reconstruction

Aware of the growing hostility, Rapier became a strong proponent of the Kansas Exodus movement of 1879, which encouraged Black migration to the Midwest. He proposed that Congress establish a land bureau to assist freedmen in obtaining land in the West and even purchased land in Kansas to help the Black community flourish. He testified before a Senate committee, exposing the exploitative nature of the sharecropping system and how it trapped Black farmers in cycles of debt. Rapier personally financed the relocation of Black families and made multiple trips to Kansas to help with their resettlement.

In 1878, President Rutherford B. Hayes appointed Rapier as a collector for the Internal Revenue Service (IRS), a position he held despite strong political opposition. He resisted attempts to remove him but was eventually forced to resign due to poor health. In 1883, he was appointed as a disbursing officer for a federal building in Montgomery but died shortly after from pulmonary tuberculosis at 45.

Following the collapse of Reconstruction, the supporters of the South created false narratives disparaging Rapier and the heroes of this era. Even though he was born in Alabama, Rapier was often described as a Canadian and a carpetbagger because he went to school in Canada and returned home after the Civil War. This false narrative empowered Americans to depict him as an evil foreign invader committed to destroying the South, and not until the 1970s, nearly 100 years after his death, did historians begin to correct the narrative.

Rapier dedicated his life to the cause of Reconstruction by leveraging political office, journalism, and grassroots activism. Despite his centrality to the success of Reconstruction, his civil rights advocacy has been largely forgotten. Rapier remains a powerful reminder of the struggles faced during Reconstruction and the continued fight to cement this era in history as a transformative one where, for the first time, basic civil rights and liberties were defined and protected by our Constitution.