The Culture, Politics, and Significance of Laughter

The profound cultural distinction between "laughing with" and "laughing at."

Long before I became a philosopher or even had any serious interests, laughter was probably the defining feature of my life.

My parents love to laugh and tell jokes and I distinctly remember deciding sometime during elementary school—probably first or second grade—that I wanted to be able to tell jokes and make people laugh too. Specifically, I wanted to make my mother laugh. My father is hilarious and could always make her laugh, and I wanted to see if I could make her laugh too, maybe even more. I liked the idea of possibly becoming the funniest person in the house and making everybody laugh.

From that moment, I started to pay more attention to my parents’ jokes and what made each of them laugh. I became bold enough to start trying out new jokes and telling stories in a more comical way. I am not sure if my parents or younger sister noticed a difference since I already laughed a lot and told plenty of jokes before this realization, but I knew that my humor and actions had more intentionality. I also noticed that my jokes and delivery got better and better, and the familial laughter got louder and louder.

Laughter has been something I have thought about for almost as long as I can remember, and while this presidential election is no laughing matter, I have become fascinated by how important laughter has become in this election.

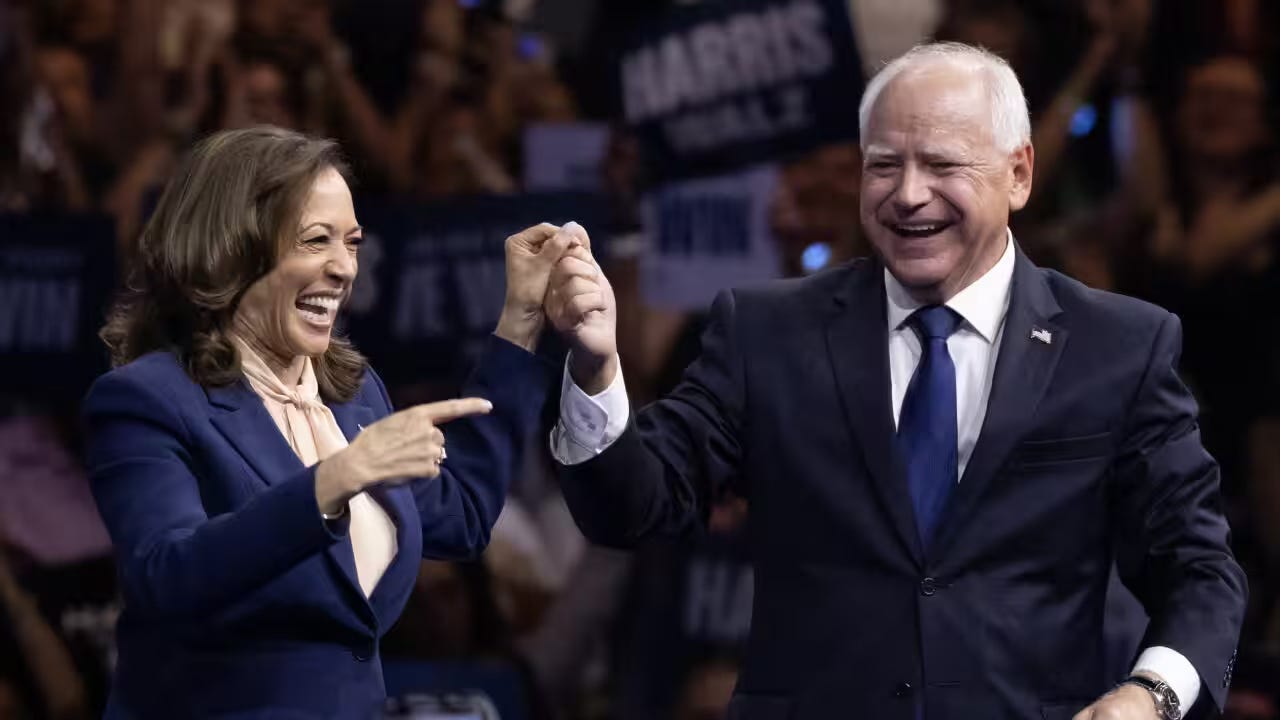

The Democratic Party’s presidential ticket of Kamala Harris and Tim Walz have become two people that progressives and democrats love to laugh with, and the Republican ticket of Donald Trump and JD Vance are people that they love to laugh at. Walz labeled Trump and Vance as “weird” and then surged in popularity to such a profound degree that Harris named him as her vice presidential running mate. Being able to laugh at the GOP ticket is not Walz’s only attribute, but in this election, it helped.

In contrast, the Republicans under Trump have never shown a propensity to laugh together and their attempts to laugh at the Democrats always feel more mean-spirited than comical. They seem almost incapable of taking a joke or delivering jokes. Their lack of humor is a serious problem and speaks to a significant cultural difference between the Democrats and the Republicans.

This cultural difference is more than the obvious fact that Republicans hate being laughed at and Democrats love laughing together. In fact, it speaks to the reality of how humor changes under a divided or a united society.

Laughing at Division

In a recent opinion piece for MSNBC titled “Trump can’t take a joke. Democrats need to use that.” historian Ruth Ben-Ghiat wrote about how authoritarians have always been incapable of taking a joke, being laughed at, or becoming the butt of jokes. Not only can they not take a joke, but they often throw in jail or execute the people who dare to laugh at them.

Considering Trump’s authoritarian tendencies and proclivity to perceive himself as being above the law, the authoritarian comparison has merit, but I think it is more important to view the dynamics of America’s political laughter through the lens of our normalized division than the threat of authoritarianism.

The act of laughing at another person amounts to a type of othering. Laughing at another person means that you consider that person to be different from and less than yourself. It can be a traumatic experience for the recipient, and it is important to distinguish between laughing at and teasing.

When someone gets teased, the general idea is that they are still part of the group, but this is a very hard balance to maintain. Someone’s friends might tease them about being short, overweight, or wearing a funny outfit, but for it to remain teasing and not bullying, the equality of the friend group must stay intact. We might laugh at someone’s flaws, but we must still be there to help support them and do our best to not cross this delicate line between teasing and bullying.

As good friends the goal is to sustain and nurture each other, and laughing at each other’s flaws and acknowledging our imperfections and vulnerabilities can be a part of sustaining a friendship. If perfection and being flawless are requirements for friendships then none of us will have any friends.

The distinction between laughing at, teasing, and bullying can be hard to distinguish within a society like the United States that has been shaped by the normalization of division. Whiteness and white identity are concepts created by Europeans so that they could have their own group that existed on their colonized land and apart from any non-European races. It is an identity that requires division and othering for its long-term survival.

Teasing is very hard to do in America and almost impossible to do between races because this society was created around fabricating almost any justification to define someone else as an Other. In America, once someone gets teased the expectation is that they have either been expelled from the group and have now become the Other, or a hierarchy within the group has been formed and the teased individual can remain within it but at the bottom of it.

This normalized division makes people increasingly isolated and friendless or cultivates toxic, abusive relationships. Our normalized division makes it harder for people to laugh together and indoctrinates people, through the trauma of social isolation and ostracism, into a culture of laughing at and bullying each other.

In Mexican writer Octavio Paz’s book The Labyrinth of Solitude he details how colonization, which he describes as a violation, has shaped Mexican culture and created a dynamic of the violator and the violated. The violation that is colonization was implemented by the violator who through their violent actions created the violated, and subsequently becomes perpetually fearful of becoming the violated. The violator does not want to become the violated because they are afraid of their own culture of violation.

Due to this dynamic, the benefactors or descendants of the violator seek to exist as impenetrable, powerful beings who show no vulnerability and exist apart from and above the Other, or the violated. The violator cannot take a joke because laughing at oneself would show vulnerability and within their divided unequal relationships vulnerability equates to weakness, and weakness could open the opportunity for being violated. Likewise, being laughed at means that one’s supremacy within the unequal binary relationship is being challenged and delegitimized, and this also equates to potentially no longer being the violator and becoming the violated.

This colonial dynamic of violator and violated can exist between husband and wife, classmates and coworkers, and employer and employee. It can influence all walks of life long before a society has become controlled by an authoritarian.

Paz was describing an aspect of Mexican culture that came from European colonization, but the parallels to American culture are abundantly clear. Trump has been convicted of sexually assaulting E. Jean Carroll and is also a convicted felon due sending hush money payments to porn star Stormy Daniels in an attempt to illegally influence the 2016 presidential election. In these instances, he was the violator, and Carroll and American democracy were the violated. The relationships he forms with everyone and everything take on the colonizer dynamics of the violator and the violated. This is one reason why Trump does not laugh.

Trump cannot laugh with people because he does not want to be with people. He wants to be above people. And he cannot tolerate being laughed at because it could shatter his façade of strength and result in him being either with or below people.

The act of laughing at someone who has chosen to exist as someone apart from other people is completely different than laughing at someone so that you turn them into the Other. In laughing at the Trump, the violator, or the authoritarian other, we are laughing at the absurdity and weirdness of intentionally attempting to exist apart from other people while claiming that everyone but yourself represents the Other.

This is an iteration of laughing at that at the very least extends from colonization to the present and challenges the normalized division of colonization and its derivatives.

Laughing with Equality

From the beginning of Joe Biden’s presidency, I remember having conversations with people about how they found Kamala Harris to be not relatable or underperforming as vice president. Few people seemed to be even remotely excited about her, and I found these critiques to be intriguing because they were in stark contrast to how she was perceived when she was primarily associated with Barack and Michelle Obama.

When the Obamas helped propel Harris’ political career, most Americans viewed her as the closest thing America could find to merging Barack and Michelle Obama into one person. She seemed fun, educated, and relatable. She could connect with people at a cultural level, and we could laugh with her just like we could with Barack and Michelle. Harris’ laugh has always been one of her defining attributes and Trump’s inability to laugh has also defined him.

However, Harris's laugh and relatability dried up and disappeared once she became the vice president, and many people questioned whether it could re-appear when she became the nominee.

I mention all of this because as her popularity soared back to her pre-Biden-levels, I often ended up explaining her rise via the popular Key & Peele “Obama Meet & Greet” skit.

In the comedy skit, Jordan Peele is playing Barack Obama and upon finishing a speech has to greet a succession of people. The first people he greets are white men and he gives them a perfectly normal business-like handshake. Home economicus would be proud of these handshakes. Next, he sees a Black man and gives him a more emotional, animated, and cultural handshake and greeting. As the skit progresses the dynamic continues and he gives stale perfunctory handshakes to the white people and emotional embraces to the Black people.

The point of the skit is not that Obama allegedly prefers one type of people over the other, but that Black and white Americans seemed to have two completely different types of greetings and that it was significant and comical that Obama could seamlessly go back and forth between the two.

The white people being depicted in this skit are being teased and not bullied. Their stale handshakes do not result in them being othered and expelled from the group.

I mention this skit in relation to Harris because Obama would seem far less relatable if he spent most of his time giving those stale, perfunctory, homo economicus handshakes, and I believe that Harris essentially suffered this fate as vice president.

Now that she can set the tone, this Key & Peele skit makes even more sense. Harris can now give both of those handshakes and lovingly relate to her diverse community as a biracial woman from a Black and Indian household who is married to a Jewish American.

However, compared to the teased white Americans from the Key & Peele skit, the progressive handshakes of today feel more emotive and culturally connected. They stayed in the group even if the handshakes were awkward. Harris and Walz laugh together and seem to have fun together. It looks to be a campaign ticket defined by laughing with.

Harris’ laughter has quickly helped to define her campaign and she has even started to openly talk about how she used to worry about how her laughter could derail her political career.

In a nation shaped by the division of colonization, the leader of the divided land is supposed to appear strong and impenetrable, and laughter represents a vulnerability that could undermine their control. Being laughed at could knock them down from their elevated position. However, being able to laugh with a leader could mean that we are less divided and more united, and now the status quo of a colonized society’s normalized division is being completely challenged.

Being able to laugh at an authoritarian, a violator, or the GOP ticket of Trump and Vance could prevent further division. Being able to laugh with a powerful politician can dismantle existing divisions and create a more equitable society. Laughter can help create cultural change. It is a good sign for equality and democracy that Harris and Walz can laugh with each other and laugh at Trump and Vance.

Harris used to suppress her laughter in public, but as she recently told The New York Times, she now understands that her laughter and joy could propel her to the White House.

Laughter, and the lack thereof, can define, divide, or unite a nation, and we can never forget that.