In 1891, more than 25 years after the conclusion of the Civil War, Missouri Senator George Graham Vest, a former congressman for the Confederacy and chief drafter of Missouri’s 1861 Secession Ordinance, argued that the framers of the Constitution never addressed whether states have the right to secede from the Union–instead claiming that this question had been “inherited” and remained unanswered since 1789. Vest pronounced that “[i]n all revolutions the vanquished are the ones who are guilty of treason, even by the historians, for history is written by the victors and framed according to the prejudices and bias existing on their side.” While similar pronouncements have been attributed to various individuals throughout history, this quote from Vest offers a particularly salient point for discussing the re-emergence of America’s White Supremacist power structure in contemporary times.

It is important to note that Vest–a member of the “vanquished” Confederacy–was never formally convicted of treason following the Civil War; instead, he returned to a position of power in the Union by becoming a three-term U.S. senator from Missouri. Moreover, a quick Google search reveals that Vest’s legacy was largely spared historical condemnation for his pro-slavery stances, with most articles instead detailing his career as a lawyer. This fact thus begs important questions: If “history is written by the victors and framed according to the prejudices and bias existing on their side,” as Vest pronounced, then why was Vest himself spared condemnation for his treasonous actions? How could a man who took up arms against the Union be welcomed back into its halls of power only a few years after the Civil War’s end?

Yet Vest was not the only former Confederate to escape accountability for his actions. On the contrary, both Jefferson Davis, the former president of the Confederacy, and Robert E. Lee, the infamous Confederate general, avoided prosecution for their involvement in the rebellion. And they weren’t rare exceptions. Indeed, although the Unionists prevailed in the Civil War, their Confederate opposition was hardly “vanquished.” Rather, the elements of the attempted revolt–which sought to cement White Supremacy as the cornerstone of society–were reintegrated into the prevailing power structures of the nation and escaped accountability for their treasonous acts. From these positions of power, the old guard of the Confederacy became virtual victors–enabling a successful effort to obfuscate the historical record, reclaim power, and ultimately reassert White Supremacy as the dominant socio-legal system throughout the nation.

The whitewashing of American history has been extensively studied and well-documented. From justifying the genocide of indigenous populations to rationalizing the brutality of America’s unique system of chattel slavery, Americans generally have not had to reckon with the brutalities of their national history. Modern efforts to update the historical record to reflect the realities of America’s past more accurately, such as The New York Times’ 1619 Project, are being met with growing, hostile resistance. Opponents of this historical re-examination assert that such efforts are themselves ahistorical and anti-American and seek instead to destroy the social fabric of this nation.

Yet, such opponents are hard-pressed to identify historical evidence supporting their assertions and, instead, resort to regurgitating the prior, refuted historical record. These opponents, moreover, have sought to impose their ahistorical perspectives through legislation, seeking to ban or mandate certain content. These efforts to obfuscate an honest recounting of America’s past do not merely provide cannon fodder in the politics of contemporary culture wars, but also serve a much broader purpose of perpetuating a cycle of American history—a cycle that inevitably restores to preeminence a White Supremacist ideology and concomitant systems of exploitation and hierarchy, albeit in subtler forms.

This “American Cycle” is rooted in the origins of the United States of America, but identifying this pattern, let alone grasping its significance, requires a clear-eyed understanding of America’s past. The mythos of American Exceptionalism obscures the brutality and exploitation that has been central to the development of the American self-concept. Further, this mythology blinds its subscribers from seeing how White Supremacy, as both an ideology and system, pervades our society today.

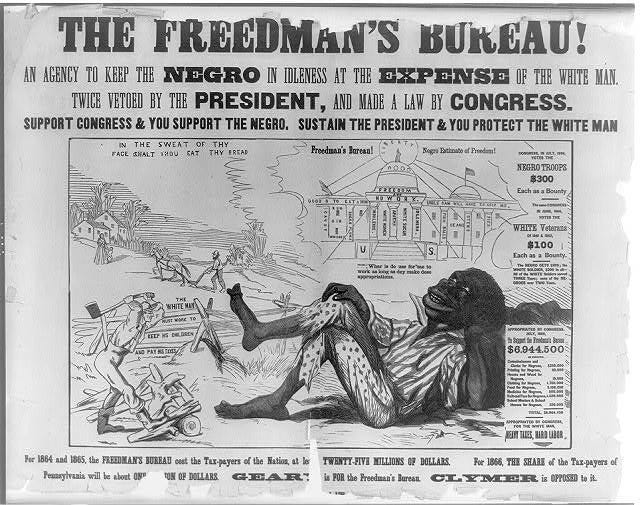

The pernicious influence that George Vest and his fellow defeated Confederates were permitted to wield enabled the thwarting of Reconstruction efforts to enfranchise Black Americans and provide them reparations. Despite the Reconstruction Amendments abolishing slavery and guaranteeing Black men the right to vote, these former Confederates instituted systems to effectively nullify these Amendments and re-establish prior systems of White Supremacy. Black Codes and poll taxes quickly eviscerated the right to vote for many formerly enslaved which was supposed to have been guaranteed by the 15th Amendment. Likewise, while the 13th Amendment abolished the chattel slavery system of the South’s plantation economy, a system of mass incarceration quickly emerged in its place to guarantee a similar supply of cheap labor. Even the 14th Amendment, which today is associated with a plethora of substantive individual rights, was initially stripped of great significance by the Supreme Court’s narrow interpretation rendered in the Slaughterhouse Cases of 1873. In his dissenting opinion on the case, Justice Stephen J. Field argued that the Court’s narrow interpretation turned the 14th Amendment into a “vain and idle enactment, which accomplished nothing and most unnecessarily excited Congress and the people on its passage.”

Each of these Reconstruction Amendments offers a window through which to view the American Cycle on full display: All three were enacted with a clear purpose of ushering in a new paradigm for America post-Civil War – a paradigm in which White Supremacy no longer was the prevailing system and ideology, but instead was replaced by a more egalitarian system that sought to embody the spirit and ideals espoused in the Declaration of Independence. Unfortunately, these Amendments have yet to fully achieve these ends, and White Supremacy has continued as a dominant force in America, albeit through varying methods and manners adapted to the prevailing social and cultural sentiments of a given era.

Yet, the Reconstruction Amendments continue to provide a viable path toward a more egalitarian future. Understanding how Reconstruction efforts were thwarted and systems of White Supremacy able to subsequently re-emerge – the first iteration of the American Cycle – can inform our historical understanding and analysis of American history more generally. Further, recognizing the pattern of the American Cycle can help to explain current and emerging political developments. Perhaps most importantly, understanding the American Cycle reveals how the absence of an actionable political philosophy capable of sustaining the hard-won progressive victories has enabled White Supremacy to maintain its hold on the American polity.

This is Reconstruction’s unfinished project – cultivating a progressive political philosophy capable of achieving the America long envisioned.