Reconstructionism & the Democracy to Come

When you receive our newsletters, you will see the phrase “the Democracy to Come” right below the banner. It is far more than a catchy slogan. This phrase is central to the philosophical mission of The Reconstructionist, and derives from the work of one of the most influential philosophers of the 20th century.

French philosopher Jacques Derrida introduced his concept of “the democracy to come” in the 1990s, and it represented a significant shift in his work because his philosophy became more actionable and less theoretical. Derrida is famous for his theory or practice of “deconstruction,” which can help us understand and examine complex concepts and philosophies. But he introduced deconstruction in the 1960s; by the 1990s, he recognized that the practice needed to evolve. This is where “the democracy to come” comes into play.

In French, “the democracy to come” is written as la democratie à venir, and à venir is a uniquely Derridian concept that highlights his propensity for neologisms. Much of Derrida’s work consists of approaching topics in a new way and discovering new things, and when you discover or do something new, a word for this new action does not yet exist. À venir is one of Derrida’s many neologisms.

The Future-to-Come

In French, “the future” can be written as le futur or l’avenir, and the verb “to come” is venir, so for Derrida l’à venir means “the future-to-come” – which is different from simply “the future.” According to Derrida, what most people consider to be “the future” is a future that is predictable or scheduled. It is a future that is plotted on a calendar. However, “the future-to-come” is unpredictable, and he considers this to be the real future or the type of future that we should embrace.

In the 2002 documentary, Derrida, he described the difference between the future and the future-to-come, l’à venir, as follows:

“In general, I try to distinguish between what one calls the future and ‘l’à venir.’ The future is that which — tomorrow, later, next century — will be. There’s a future which is predictable, programmed, scheduled, foreseeable. But there is a future, l’à venir (to come) which refers to someone who comes, whose arrival is totally unexpected. For me, that is the real future. That which is totally unpredictable. The Other who comes without my being able to anticipate their arrival. So if there is a real future beyond this other known future, it’s l’à venir in that it’s the coming of the Other when I am completely unable to foresee their arrival.”

In the United States’ hyper-individualized culture, the concept of l’à venir can be frightening because our relative lack of community and normalized division make it harder for us to cope with unexpected or unpredictable situations.

For example, the simple act of a child catching a cold for a couple of days and not being able to attend daycare or school can cause a mini-crisis in America if the parent is unable to take off work, or cannot find or afford for someone to watch their child. Also, it is common for parents to bemoan how their young child is hard to control, and how the natural, unpredictable existence of a young child can become a source of near-constant anxiety because their unpredictable existence is disrupting the orderly, planned future that the parent seeks to create.

We all know that children catch colds, but we cannot anticipate their arrival. Likewise, we all know that children are unpredictable, but a yearning for the predictable remains. American individualism means that the future-to-come creates anxiety and worry because we are often forced to manage the unpredictable on our own. Our isolated norm means we shun and fear an unpredictable future because we know that we may not have the resources and support structure to manage it.

The fear of the future-to-come can incline people to search for stability and security from the past, and to strive for a future that is nothing more than a modified continuation of the past. The disastrous conservative legal doctrine of originalism is one American iteration of this propensity. Donald Trump’s “Make America Great Again” slogan is another. The recent cultural obsession with “tradwives” is another. American individualism creates a yearning for the past and a fear of the future-to-come, and this dynamic also undermines the fabric of American democracy.

The Democracy to Come

As Derrida developed his concept of l’à venir, he also applied deconstruction to democracy and employed l’à venir in his analysis. In so doing, he observed that the future-to-come is a vital part of any successful democracy.

According to Derrida, a democratic state is not a static end goal, where the creation of a democracy means that society has arrived at an ideal, utopian state where the institutions and structures of a democracy would preserve it. In fact, he believed that democracy was the inverse of this commonly held belief.

For Derrida, a democracy was not self-sustaining, but was actually “autoimmune,” in that all democracies have, or must have, the capacity to destroy themselves. An autoimmune disease occurs when one’s immune system mistakenly targets healthy, functioning cells as if they were a foreign object that needs to be destroyed, and Derrida argued that autoimmunity was an essential part of a democracy because when the people, or demos, shape the government it becomes inevitable that they will at some point misdiagnose a healthy, functioning aspect of their democracy as a destructive foreign object that needs to be destroyed. Yet if a democracy systematically limits or oppresses its people in the name of self-preservation, it will instead become an authoritarian state and no longer a democracy.

Arguably the most obvious example of autoimmunity destroying a healthy, functioning democracy is the rise of the Nazi Party in Germany. Adolf Hitler and the Nazi Party legally rose to power within Germany’s democracy via an agenda of autoimmunity that inaccurately diagnosed German Jews and Germany’s parliamentary government, or the Reichstag, as the nation’s core problems that needed to be eradicated.

On February 27, 1933, only four weeks after Hitler was inaugurated as Chancellor, the Reichstag was set on fire, and it is almost universally accepted that Hilter and the Nazi Party set fire to Germany’s parliament to both destroy the seat of government that they despised and to use it as a “false flag” operation allowing them to blame their adversaries for the attack and generate public support for the Nazi Party. Over the next decade, their support and power only grew, culminating, in 1941, with their autoimmune Holocaust agenda that would kill roughly six million Jews, about two-thirds of Europe’s Jewish population.

The tendency toward autoimmunity within a democracy therefore means that a democracy should never seek or become a static, final, end state. Democracy instead should be a continual process and practice that requires an experiential recognition and understanding of good and evil. The capacity of the demos to engage in good practices remains the best way to prevent, combat, and rehabilitate the autoimmune disease that also must exist within a democracy.

If a democracy struggles to differentiate between good and evil, it will only be a matter of time before it devours itself.

Reconstructionism and the Democracy to Come

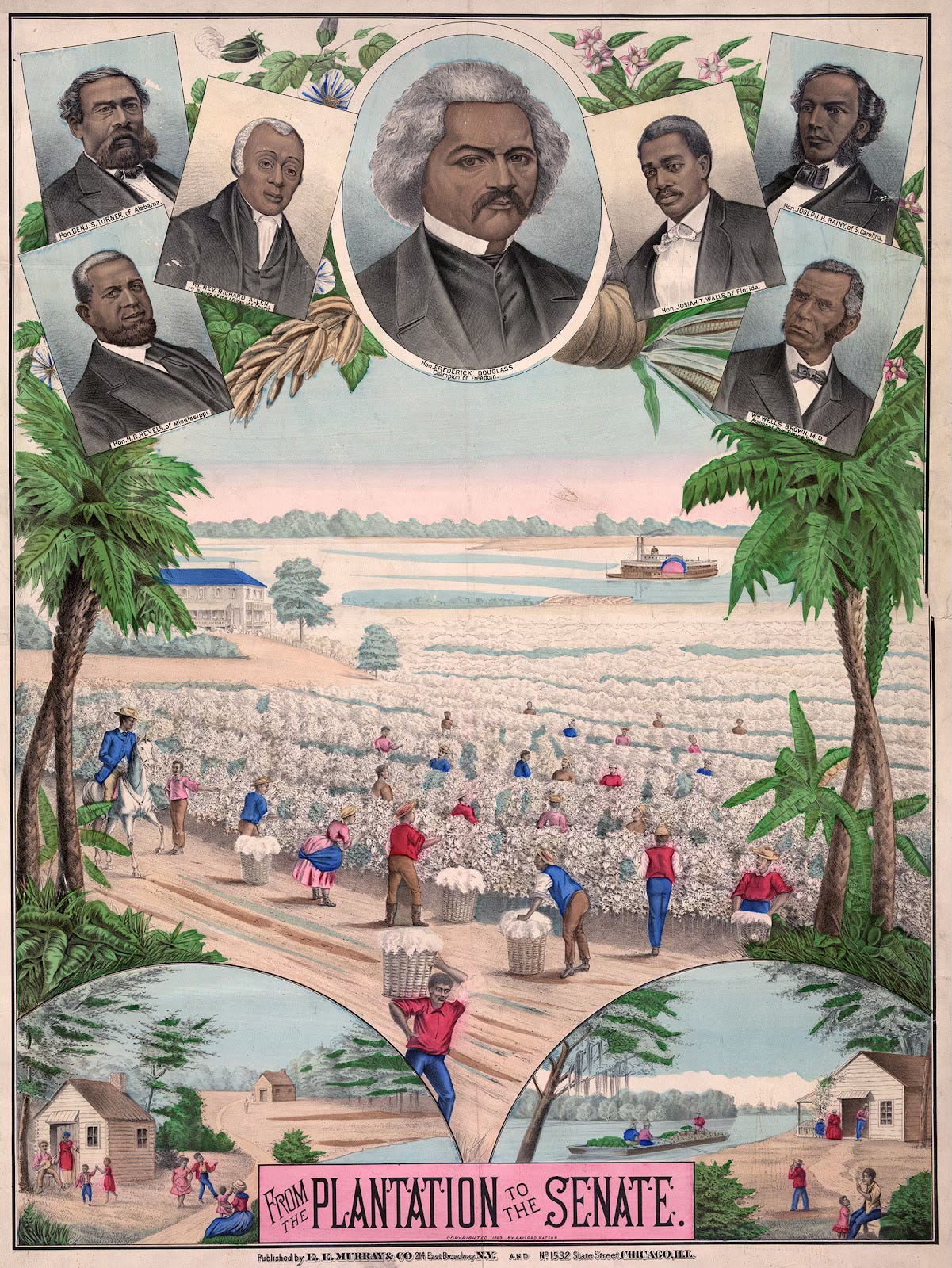

The future-to-come is the unpredictable arrival of the Other, and within the American context, Reconstruction from 1865 to 1877 and the presidency of Barack Obama both fit this description. According to my theory of the American Cycle, these eras represent the United States’ two eras of Reconstruction.

Before Obama’s national-debut speech at the Democratic National Convention, in 2004, the American public would never have predicted that we would have a Black president by 2009. Obama’s arrival was totally unexpected, and he allowed the American public to believe that we could create something new and successfully navigate uncharted territory. This iteration of the future-to-come inspired the American public and gave our society hope.

Likewise, if we explore Reconstruction the same dynamic emerges. The emancipation of Black people and suffrage for Black men was not part of the predictable future of the United States. Just before the outbreak of the Civil War, emancipation was beyond the contemplation of Supreme Court Chief Justice Roger Taney in his 1857 opinion in Dred Scott v. Sandford, in which he interpreted the original intent of the framers of the Constitution as believing that Black people were “altogether unfit to associate with the white race, either in social or political relations, and so far inferior that they had no rights which the white man was bound to respect.”

If, in 1857, Black people had “no rights which the white man was bound to respect,” it was certainly unpredictable and unexpected that they would be citizens with voting rights only a decade later.

Derrida did not talk about Reconstruction in his work and he passed away in 2004, so he never saw Obama become president, but according to his work Obama’s presidency and Reconstruction could be seen as the “real” future, the future-to-come, l’à venir, and the type of future that a democracy needs to survive.

I find Derrida’s concept of l’à venir so compelling when analyzing America because the normalization of racial division and oppression has always been a bedrock of American society. Due to America’s ethnocidal roots, people of color, or the Other, will inevitably combat this divisive status quo, but since division and inequality are the norm, the arrival of equality, unity, and the Other will always be unpredictable and unexpected.

The autoimmunity of America’s democracy attacks diversity, equality, and any concept that could transcend white dominance because we have always misdiagnosed the healthy, functioning part of our democracy as a cancer that must be destroyed.

To effectively combat America’s autoimmunity, we must understand that the goodness of this nation stems from our two eras of Reconstruction and the eras of Abolition that preceded them. Due to Trump’s MAGA movement and originalist legal theory, however, America’s autoimmunity continues to devour our democracy.

Reconstructionism, and an appreciation of the goodness of Reconstruction, can prevent America from devouring itself, allow us to continue the practice and process of democracy, and empower us to create the democracy to come.