The Commons • noun • (thee caw-minns)

Definition: a collective space without ownership where people share physical and cultural resources for the benefit of their entire community.

Origin - English

Join us today at 5pm on SCL’s Instagramfor an IG Live about this week’s word!

This is a great opportunity to ask questions, learn more, and become part of the conversation!

To help sustain and grow The Word with Barrett Holmes Pitner we have introduced a subscription option to the newsletter. Subscribers will allow us to continue producing The Word, and create exciting new content including podcasts and new newsletters.

Subscriptions start at $5 a month, and if you would like to give more you can sign up as a Founding Member and name your price.

We really enjoy bringing you The Word each week and we thank you for supporting our work.

Since much of the work of SCL consists of highlighting the ethnocidal foundations of American society, our work can at first seem pessimistic. It can seem as though we mostly highlight problems, not solutions. Our position is this: in order to even begin the process of formulating or uncovering solutions, you must first acknowledge the full scope of the problem. Our awareness of ethnocide helps us understand the severity of the problem, and in this week’s newsletter we will discuss a potential solution.

The commons does not exist in the United States, yet much of our mainstream discourse today consists of yearning for a sense of community and commonality to bring about peace and stability within our chaotic society. For example, following mass shootings, Americans ask for “common sense” gun control legislation, but how can we have “common sense” when our ethnocidal divisions prevent the cultivation of a common people and the commons? Americans yearn for common sense and to transcend our divisions, but the absence of the commons in our society repeatedly impedes our ability to do so.

We live within an ethnocidal society built upon the normalization of sustained division, yet we also know that our divisions are the source of our problems. However, since America has never existed without these divisions, we have few reference points and nearly zero experience cultivating a society that is both absent of and prevents our ethnocidal divisions.

The commons is a concept that can transcend ethnocide, and unsurprisingly Americans have long believed the commons to be a tragic concept that is destined to fail.

The Joy of the Commons

When I first began my work regarding ethnocide and how to transcend it, I focused on the importance of collective gathering spaces. The idea of the “town square” became an integral part of my philosophical work. The town square is simply a wide open space, normally in the heart of a city, where people are encouraged to coexist, to live together.

It does not exist to derive profit, but embrace existence. Town squares are often the only places where people can gather in opposition to authoritarian regimes as they fight for their existence and against oppression.

American cities mostly do not have vibrant town squares. The central location of a town square often occupies valuable real estate, and our capitalist society has far more language to encourage the manipulation of land for profit instead of existence. Also, America’s individualistic impulses encourage people to believe that freedom resides within the private spaces one owns instead of within the public, communal spaces devoid of ownership.

America’s façade of culture advocates for the removal of public, communal spaces, but in an example of mauvaise foi, or bad faith, Americans do not believe that we dislike public spaces because our culture does embrace the preservation of parks.

We embrace public spaces such as parks as a source of recreation, but recreation is often a luxury and not a necessity. True public spaces are a necessity, and this brings us back to the commons.

As recently as the 18th century in England, the commons existed as public land that people would collectively farm. These farmers used the commons to grow the crops that they needed to survive. There was no desire to make a profit off of the land. Instead, the goal was to collectively cultivate the land so that it would provide sustenance for all members of the community in perpetuity.

One farmer might specialize in one crop and another farmer would specialize in a different crop. Their crops might grow side by side, feeding off of each other’s nutrients via practices of co-planting that have been cultivated by cultures around the world for thousands of years. When the harvest would come, the farmers of the commons would share their harvests with each other for the betterment of the community, and they were also able to sell their extra harvests.

The commons might sound too harmonious or impractical because disputes would inevitably arise, but it is important to note that the commons was always heavily regulated. Sustaining a balance requires a lot of work, and it can only succeed if the members of the commons both understand and agree to the philosophy of the commons.

It is a shared, collective space without ownership where participants farm not just for the benefit of their family, but for their entire community, which becomes an extended family.

The philosophical foundation of the commons is not too dissimilar to how many Indigenous peoples in North America had no concept of private property prior to colonization. The land belonged to everyone, and therefore everyone had a cultural obligation to work together to sustain the land and their collective existence.

For example, if a tract of land had a river running through it, one group of people might oversee the fishing of the river, another might grow crops in another part of the land, and another group of people might hunt on the land; but no group of people owned all of the land.

This communal connection to the land is the foundation of culture, and the commons is an integral part of a sustainable culture. Common land for sustenance, recreation, and collective gathering are vital parts of a healthy society, and tragically, the United States’ ethnocidal foundations mean that we are lacking in all of these communal spaces.

The Tragedy of the Commons

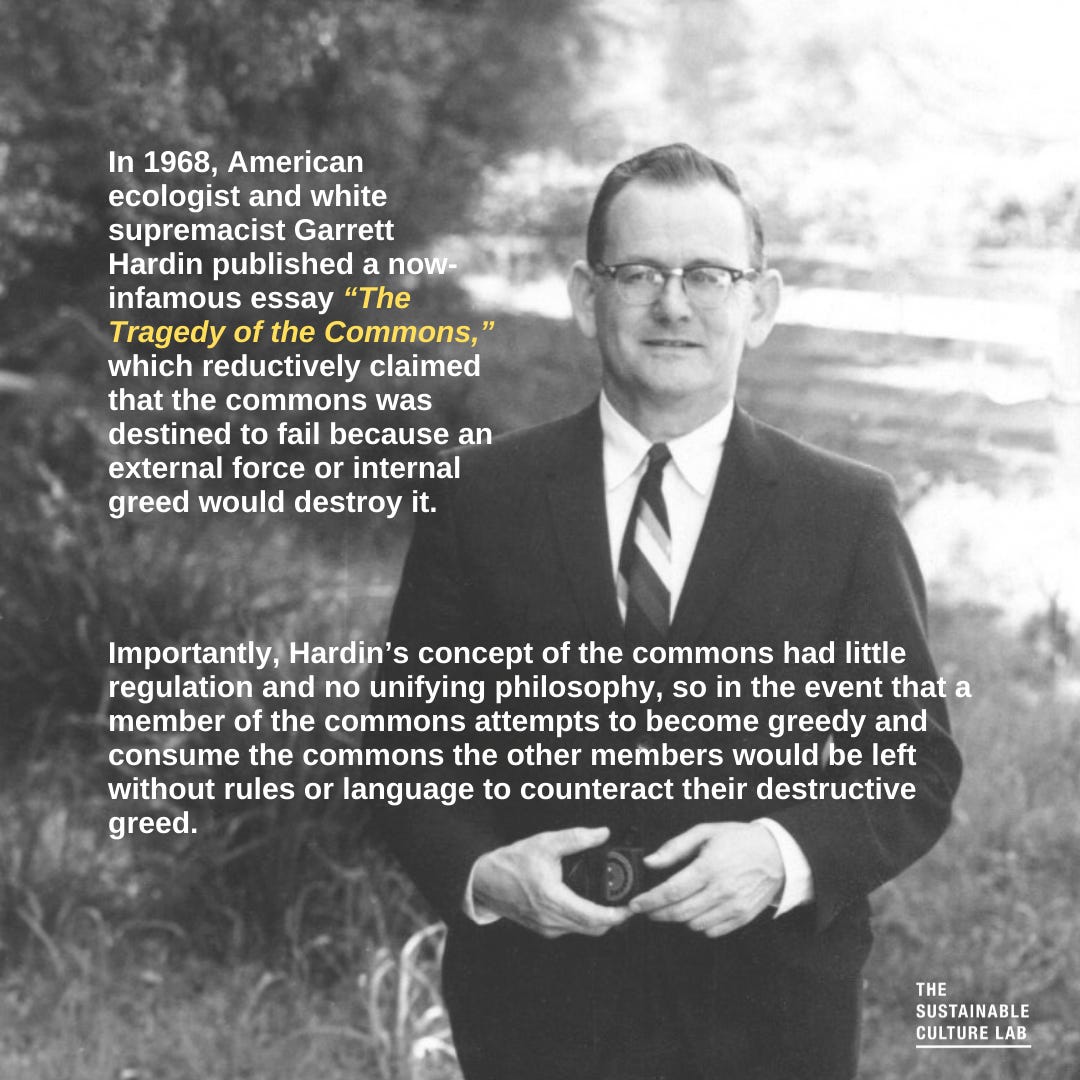

In 1968, American ecologist and white supremacist Garrett Hardin published the essay “The Tragedy of the Commons,” which reductively claimed that the commons was destined to fail because an external force or internal greed would destroy it.

Importantly, Hardin’s concept of the commons had little regulation and no unifying philosophy, so in the event that a member of the commons attempts to become greedy and consume the commons the other members would be left without rules or language to counteract their destructive greed.

Additionally, many modern critics of the commons perceive the commons to be primitive and inefficient because the land’s primary use is not to generate wealth. Commoners, or members of the commons, subsequently are looked down upon by Hardin and other detractors of the commons because they prefer to grow food for their survival instead of accumulating wealth.

Hardin’s criticism of the commons argues that greed equates to an unstoppable force that will inevitably destroy the commons from either the inside or the outside. In Hardin’s eyes, the commons is tragic because according to him greed will always triumph over existence and survival. Hardin’s perspective is incredibly ethnocidal, divisive, and capitalistic.

In England, the commons was incrementally destroyed beginning in the 18th century as privatization and industrialization became the cultural norm. Instead of valuing public land that people cultivated for their survival, the English prioritized the new concept of private property, where the owner could do whatever they wanted with their land. The opportunity to do whatever one wants with their land is often described as a “freedom,” and this notion of freedom was clearly exported to the British colonies.

In the United States, ownership has often been considered a pathway to freedom, but as an ethnocidal society that embraced the vast wealth created by chattel slavery, we also know that American ownership also includes the denial of freedom.

American colonizers engaged in the ethnocidal transatlantic slave trade, so that African people would be forced to cultivate the land of North America so that it would generate wealth for white colonizers. The land never existed as a source of sustenance and cultural survival, so the United States never developed a commons.

Additionally, the required divisions of ethnocide meant that communal gathering spaces could not truly exist in America. If people of color were allowed to collectively gather then they potentially could band together and liberate themselves from the ethnocidal white oppressors. Likewise, if white people and people of color could collectively gather then interracial coupling would grow expenentially and now whiteness would progressively diminish.

The United States’ ethnocidal foundations meant that the commons could never take root because it would dismantle white supremacy and American capitalism, both of which depend on embracing privatization and greed.

Hardin’s racist, greedy culture viewed the commons as a tragedy because he knew that it was inevitable that people like him would try to destroy it.

In order to transcend ethnocide and liberate ourselves from the horrible, destructive views of men like Hardin, we must embrace public space for recreation, communal gathering, and most importantly for food and nurturing our collective sustenance.