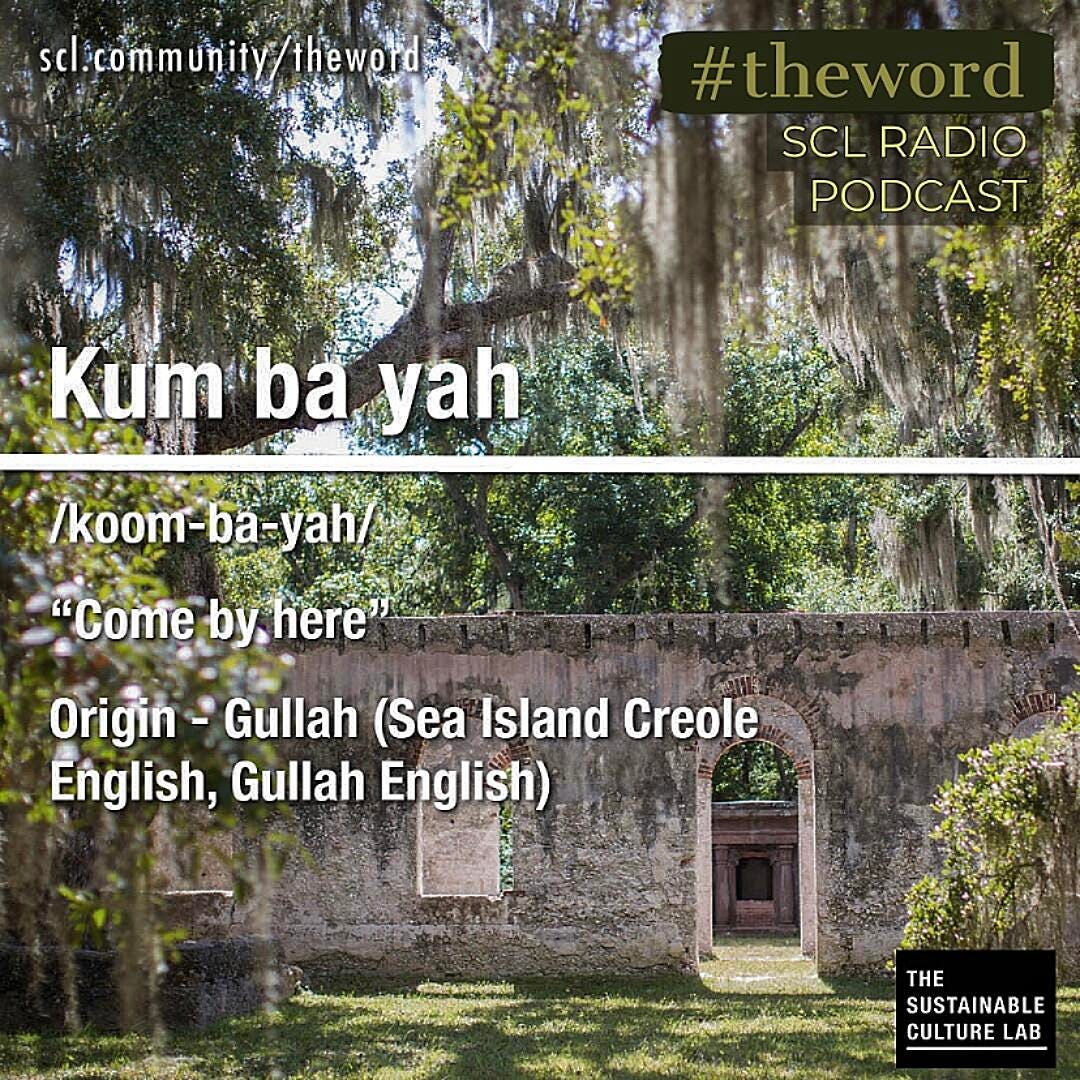

Kum ba yah • (koom-ba-ya) • phrase

Definition: “Come by here”

Origin: Gullah (Sea Island Creole English, Gullah English)

Many people don’t know this about me, but my mother’s side of the family has lived in Charleston, South Carolina as free persons of color (FPC) since the beginning of the 1800s. These people, my mother's side of the family, are known as Gullah Geechee people, and Charleston has a Black history that is distinct from much of the South. Not only has Charleston had a vibrant FPC community since the founding of the United States, but it also has a series of islands off the coast that FPCs and enslaved Blacks escaped to in the hopes of liberating themselves from ethnocidal oppression. The Sea Islands provided a refuge that few Blacks, or Freecano people, ever experienced in America.

Within the sanctuaries of the Sea Islands and the FPC communities on the mainland, Black people were able to cultivate a new culture that retained many remnants of their various African cultures. Many Gullah Geechee people speak with an accent that is more akin to the Caribbean than the United States due to the preservation of an African cadence. My mother has this accent, and to this day, people still think she is Jamaican.

Many are also unaware that the word, phrase, and song “Kumbaya” comes from the Gullah people. The fact that most Americans know this word, but very few understand its history is another example of ethnocide’s destruction of culture and its tendency to make the meaningful meaningless. The culture of Gullah people also represents the distinct, vibrant, and resilient culture of the ethnocidee within ethnocide.

“Oh Lord, Come by Here”

What is commonly known as “Kumbaya” is actually spelled “Kum ba yah” in Gullah English, which translates to “come by here.” The word/phrase “kum ba yah” has a clearly defined meaning that could not be more different from the amorphous and harmonious interpretation of the word that we hear today.

“Kum ba yah” is a Gullah spiritual song that implores the Lord to “come by here” because the Gullah people are in need of divine intervention to rescue them from ethnocidal terror. The lyrics of the song can vary from person to person due to the numerous reasons why a Black person in the South would need the Lord to “come by here.” One version sings “Hear me crying, my Lord, kum bay yah,” and another sings “Now I need you, Lord, come by here.”

“Kum ba yah” is a plea for help from the Heavens that Gullah, and Black, people have needed to articulate in order to survive in America. Without the hope of divine intervention, the nearly inescapable specter of ethnocidal oppression could leave a person or a people feeling hopeless.

“Kum ba yah” is both a song and a prayer that has been expressed by Gullah people for generations. However, as ethnocide continued in America as the norm, it would be fair to question if the Lord ever arrived.

The Extraction of Meaning

When Americans say or sing “kumbaya” today, the meaning of the word has been completely erased. Nowadays “kumbaya” seems to mean some sort of harmonious togetherness. If Democrats and Republicans agree on something without the normal tension and bickering, that could be a kumbaya moment. If children are fighting, it isn’t out of the ordinary for someone to tell them to hold hands and sing “kumbaya” to restore peace. What “kum ba yah” means today could not be further removed from what the literal words are actually saying, and now we must wonder how and why this error occurred.

The two oldest recordings of “kum ba yah” were collected in 1926, but it is unknown exactly when these recordings took place. Yet despite this documentation and the known connection to Gullah people, the person commonly associated with writing and owning the copyright of the song is a white man named Marvin Frey.

He was an evangelical minister and he claims to have written the song, which he titled “Come by Here,” in 1936, a decade after the first known recording. Frey claims to have been inspired to write the song after hearing a prayer by “Mother Duffin,” an evangelist he heard in Portland, Oregon. Nothing is known of “Mother Duffin.” Maybe she was a Gullah Geechee person who sang “kum ba yah” within earshot of Frey, and upon hearing her prayer for help, Frey was “inspired” to write down the song and claim this part of her culture as his own.

Frey may not have considered his actions to be a cultural theft. He may have been totally unaware that the beauty of her African cadence and Gullah English dialect obscured the meaning of the song. He could have viewed his actions as sharing this beautiful, yet tragic song with the world. Yet regardless of his intentions, he took a song that Black people used to pray to the Lord to save them from white ethnocidal oppression, and presented it as his own creation that was used to comfort and empower other white people.

The story of Frey, and the evolution of “kum ba yah”, demonstrates how ethnocide is not always perpetuated via malicious intent. Ignorance, the absence of culture, and the normalization of taking the culture of others create a societal norm where well-meaning people continue ethnocide not because they are evil, but because they are accustomed to doing so.

“Kum ba yah” Today

Following the whitewashing of “kum ba yah” by Frey, more and more white artists began singing the song, and over time it evolved into today’s meaning. In 1958, celebrated singer Pete Seeger did his own recording of “Kumbaya.” Folk singer Joan Baez also recorded his version in 1962, and during the 1960s it came to represent unity and togetherness during the civil rights movement. What’s ironic is that the coming togetherness promoted by this song still harbors a strange white ownership behind the scenes. White Americans now emplored Black people to sing a culturally Black song but with the new white meaning, and to view this coming together as a sign of progress. These “Kumbaya” moments did not have malicious intent. There was not a perverse agenda to whitewash Black culture, forcefully feed it back to Black people, and then have them thank white people for the cultural extraction; but this is what has happened and has been happening in America for decades.

The paradox about “kum ba yah” today is that the prayer has always been about the liberation from ethnocide; however, that liberation also includes white people because they too need to be liberated from their norm of extracting cultures. American ethnocide feeds off of everyone and makes people who don’t have malicious intent do ethnocidal things. Even well-intended ethnocide is still ethnocide, and the change from “Kum ba yah” to “Kumbaya” demonstrates how normalized it is in our society to extract, consume, and erase other people’s cultures.

So far, America has heard the cries and prayers of “kum ba yah” but never understood it to be a cry for help. We can gradually begin to break away from our ethnocidal cycle by increasing our awareness of cultural issues and appropriation, and understanding that this cry continues to this day in the Black Lives Matter movement. We can say no to the systems and ideas that came before us and actively decide to help Black people, all people of color, and marginalized groups to live equitable, healthy, and free lives in America.